This is the third installment about the feasibility of electric buses, and the factors that render them so or not so.

The first installment dealt with a small mid-west community that obtained its first electric schoolbus for free, through an unusual grant program – and had a hard time figuring out how to handle it. This challenge was compounded by the battery not working – and it taking from September until the Spring for the manufacturer to fix it. But this experience was viewed differently by different members of the community. And the costly charging station, amortized by a single vehicle, was an extravagance that greatly strained this community’s resources.

The second installment dealt with Rhode Island’s difficult implementation of a small fleet of electric buses not justified by the trivial volume of pollution they saved, and compounded by an initial fleet whose batteries delivered a third of the holding capacity they promised. Then a larger replacement fleet’s use was integrated into a land use project that was both costly and tricky politically, and forced some other controversial trade-offs related to land use. All the vehicles were deployed on a single route – the state’s fattest — to “make the numbers look better.” But even with this concentration, this tiny fleet did not remotely justify the four $22M charging stations needed to support it, particularly, as noted, given the infinitesimal percentage of the State’s pollution its tiny fleet of clean-diesel buses contributed to it. Expanding the system would make even less sense, since more charging stations would be needed.

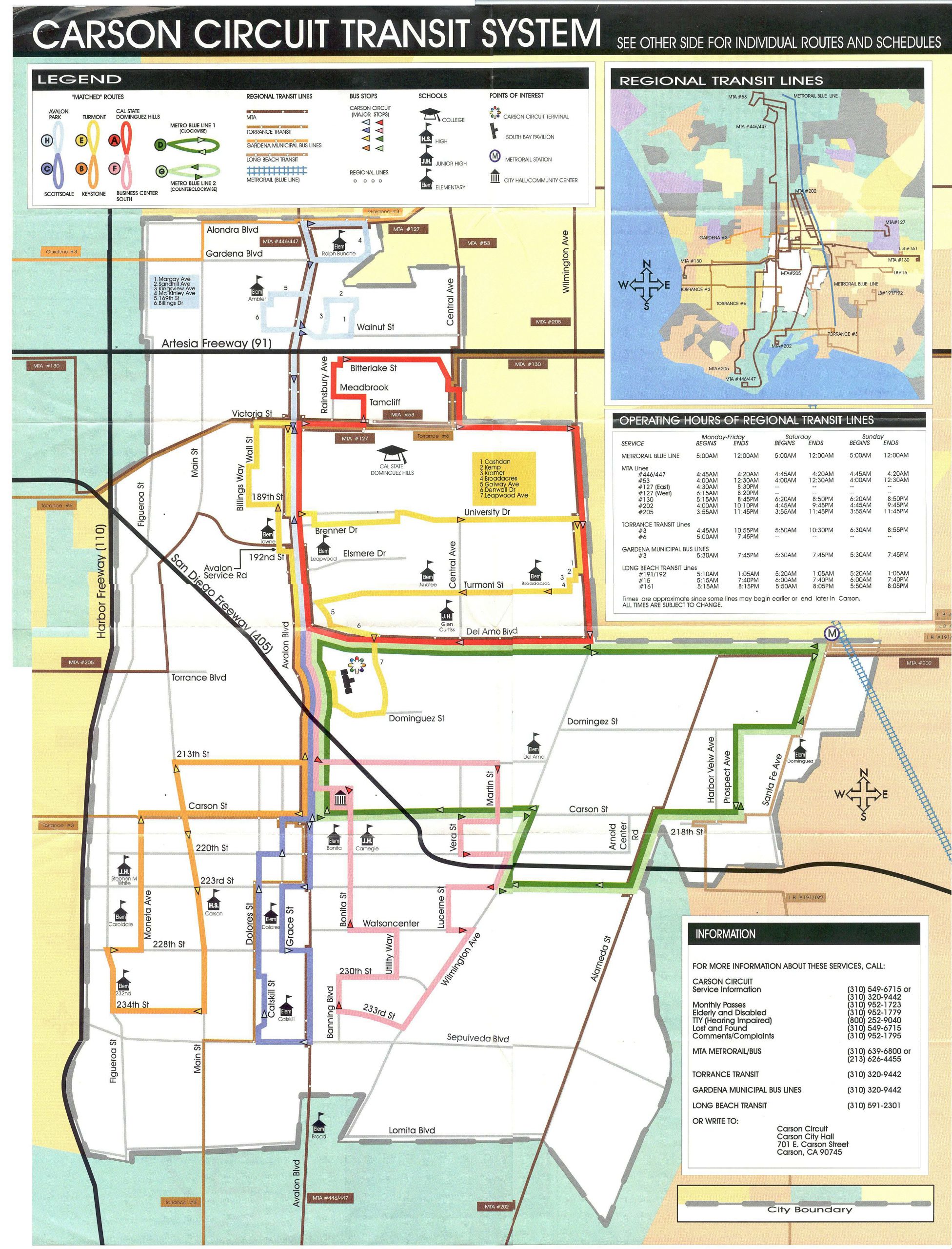

This installment describes a city which currently does not deploy any electric buses, but whose “system design” and surrounding air quality might justify a single charging station – all that would be needed to support the entire fleet. I am talking about the Carson Circuit Transit System in Los Angeles County – a system I and two others designed in 1982, and which I redesigned in 1992. The original redesign (1992) can be seen here

The system’s current configuration may be seen at Wikipedia – Carson Circuit Transit System. (I did not design the dysfunctional purple route shown, which does not connect to the system’s center, like the others; some local city council woman drew it, with a crayon, on a large sheet of paper, and presented it at a city council meeting in 1992; the hapless council chose to add it to the system — to my horror and to the horror of the city’s director of transportation).

Like issues noted in previous installments about electric buses. the challenge of protecting the technical integrity of a transportation system designed by group of experts from the whims of political amateurs is a formidable task – even without initiating innovations like electric buses. The terrific director of transportation in Carson in 1982, who shepherded the system through its first 25 years of operations, was a savant; but she survived the political environment surrounding her with a prize-winning amount of patience and tolerance, and an overabundance of physical meditation. Yet, again, we are not even talking about electric vehicles. We are only talking about transportation officials protecting the integrity of their systems from interference by amateur politicians with no remote understanding of any principles of transportation (see Principles of System Design).

System Design

This terminology is almost extinct in modern transit, largely reflecting the intrusion of route design software into the transportation planning environment, and the increased replacement of decisions by technical experts with decisions by people with no expertise in the field (see again Principles of System Design) other than “working the robots” and the rigid programming constraints of routing and scheduling software.

But even within this difficult environment, electric vehicles might make some sense in a city with a transportation system like the Carson Circuit. As one can see from either graphic (this is easier to grasp from my map at Carson Map), this is what is known as a “timed transfer pulse” system. In this system, every route (except for the purple intruder) converges at the rear of a large mall at the city’s center – all at the same time, roughly every 35 minutes. Passengers then have about five minutes to transfer to another route, if needed – a small, reliable transfer period that poses no significant interruption of service and allows one to get from one end of the City to another in, at most, an hour and 15 minutes. But from an electric bus perspective, this system’s routes would effectively require only a single charging station – although likely a large one with eight pumps. And each quick charge need only keep the vehicle moving for 35 minutes. Both factors are rare, if not unique, for a transit system. But they do address the three key problems transit systems with electric vehicles face: The cost of charging stations, the time for charging, and the mileage each vehicle can travel on a single charge. It would seem hard to optimize these variables better than in a system that did not possess the Carson Circuit ‘s unique characteristics.

Cons and Caveats

At first glance, the pollution from a nine-bus system with clean-diesel vehicles would seem to be an asterisk compared to the pollution from hundreds of thousands of vehicles operating within or passing through the city on three of Los Angeles County’s most congested freeways. And this does not even include the heightened pollution in the city as thousands of rush-hour motorists use the city’s streets as shortcuts when the freeways become congested.

But that is only the narrow view – and a reason that a system like that being described should include county funding as well as city funding — reflecting the pollution characteristics of Los Angeles County as a whole. One may argue about what percent of the County’s total pollution is caused by the County’s 2300 buses. But the fact that the overall pollution is so increasingly intolerable, the conversion of nine clean-diesel buses to electric buses relying on only a single charging station may justify its contribution – even while a somewhat expensive one. But that cost might be lessened if other regional buses can charge their vehicles during the in-between times at this single, nine-pump station – or use it for overnight and Sunday charging, when the Carson Circuit does not operate. And it could be further amortized if it could also charge an occasional automobile – thousands of which park at the mall where the system’s center lies, and which is free of buses for 35 of every 40 minutes.

Interestingly also is the fact that the charging station would be adjacent to a huge mall – and the station might be super-charged itself from power otherwise used inside the Mall. If such scaling is technically possible, and feasible, it will extend the capabilities of the bus-charging station even further.

Electric, Meh

Based on the three models illustrated in this and the former two installments, it is clear that electric buses make no sense practically anywhere. Much-needed exceptions may include cities like New York City or Chicago, where one must electrify virtually everything to ensure the ability to breathe easily two decades from now. But even in these environments, routes would have to be reconfigured to reduce the number of costly charging stations. In contrast, there would be precious few opportunities in, say, Los Angeles County, to do this — where the routes spread out in all directions to cover a 4084-square-mile area, with dozens of transit agencies rendering the type of coordination needed to justify even a handful of charging stations almost an impossibility in such an environment – not even considering the politics.

This might be possible with a king. But Los Angeles County does not have one, and the head of its transit system – the LACMTA – just let a nationwide broker manage its paratransit system. So finding more than a handful of opportunities in this type of environment – if any—would be a daunting task – except, ironically, for the Carson Circuit. Yet there are a few local systems in this County – Long Beach, Santa Monica come to mind — as well as a few spots in the center of Los Angeles — where a charging station might be marginally justified if routes are configured to optimize their usage. Unfortunately, route configurations throughout this County are largely frozen in time – and the magnitude of route designs changes needed to optimize both the cost of the vehicles plus the extravagantly expensive charging stations (often exceeding $20M apiece) would not likely materialize in this 82-city political environment.

In contrast, the conversion of personal occupancy vehicles (POVs) to electric is a necessity. But at the same time, the enormous volume of traffic concentrated in urban environments – where many would park for hours — could make the installation of hundreds of charging stations – or perhaps thousands – feasible. But again, feasibility here is borne of necessity. Without that necessity, and the other benefits from not relying on finite fossil fuels, no fleet of electric vehicles could be justified given their costs. We simply have no choice.

But the same is not true of electric buses – whose masses compared to automobiles translate into far more charging time and far less mileage per charge. At the same time, the technology to use a bus-oriented charging station to charge other types of vehicles is not likely fully developed. When it begins to become feasible, planning options that are patently unfeasible now may begin to make sense, and may lend themselves to route and schedule designs that help amortize the cost of the charging stations – assuming we can actually design routes and schedules coherently. The latter may be the greatest challenge of them all.